Types of Shells

Not just bash shell

Intro

Once we compromise a system and exploit a vulnerability to execute commands on the compromised hosts remotely, we usually need a method of communicating with the system not to have to keep exploiting the same vulnerability to execute each command. To enumerate the system or take further control over it or within its network, we need a reliable connection that gives us direct access to the system’s shell, i.e., Bash or PowerShell, so we can thoroughly investigate the remote system for our next move.

We can connect to a compromised system is through network protocols, like SSH for Linux or WinRM for Windows, which would allow us a remote login to the compromised system. Nevertheless, the other method of accessing a compromised host for control and remote code execution is through shells. As previously discussed, there are three main types of shells: Reverse Shell, Bind Shell, and Web Shell. Each of these shells has a different method of communication with us for accepting and executing our commands.

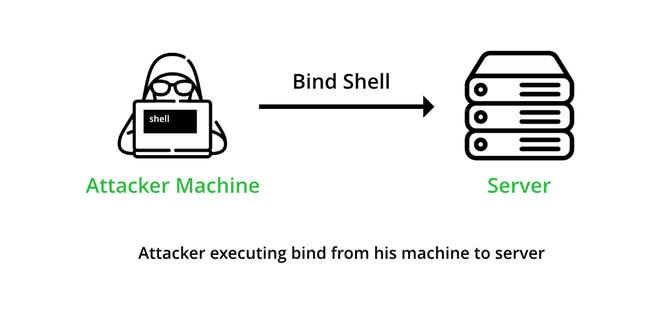

Bind Shell

The concept of a bind shell is that the attacker’s machine acts as a client and the victim’s machine acts as a server, which opens a communication port and waits for the client (attacker) to connect to it, and then issues commands to be executed remotely on the victim’s machine.

–> Bind shell – Waits for us to connect to it and gives us control once we do.

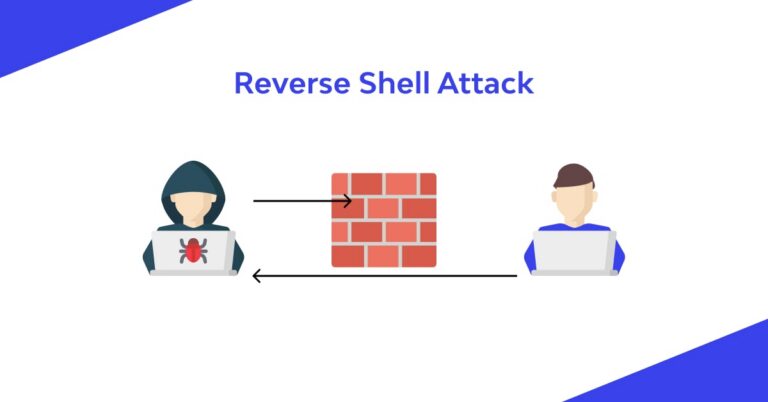

Reverse Shell

A Reverse Shell is the most common type of shell, as it is the quickest and easiest method to obtain control over a compromised host.

To make it clearer, I’ll use an example. As you read in the BindShell section, using a bindshell isn’t very common because the host that listens for a connection is the target machine, while we are the one initiating the connection. Looking at the diagram below, you can see what happens if a bindshell is used but a firewall sits in front and blocks it — or if you’re attacking from an external network zone: how can you connect to a server with a private IP behind a firewall? Do you need to compromise the firewall to create NAT for it? It’s complicated.

A reverse shell works the other way: you act as the listener and control your attack infrastructure (for example, by hosting a service on port 443). The target will call back to you, which resembles a normal outbound connection from LAN → external network. Nevertheless, you must pick the port for your attack machine carefully, because network admins often restrict outgoing traffic to only well-known ports.

–> Reverse shell – Connects back to our system and gives us control through a reverse connection.

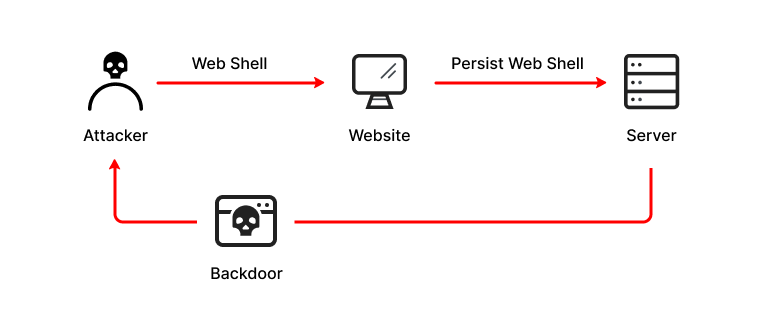

Web Shell

Another type of shell we have is a Web Shell. A Web Shell is typically a web script, i.e., PHP or ASPX, that accepts our command through HTTP request parameters such as GET or POST request parameters, executes our command, and prints its output back on the web page. A distant aggressor can utilize a web shell to perform pernicious orders and take information on the off chance that it is effectively embedded into a web server.

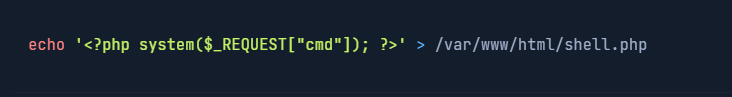

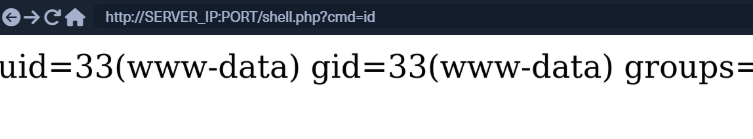

For example: if I find an unrestricted file-upload vulnerability, I would upload a web shell that executes system commands and displays the output on the webpage. After preparing the web shell, I upload it — depending on where uploads are stored it might land in the webroot, or I may need to discover its location (using fuzzing). Suppose I can upload my web shell to the webroot at /var/www/html/shell.php.

Once we write our web shell, we can either access it through a browser or by using cURL. We can visit the shell.php page on the compromised website, and use ?cmd=id to execute the id command:

The Payload All The Things page has a comprehensive list of reverse shell and bind shell commands we can use that cover a wide range of options depending on our compromised host.