When we don’t specify any parameters, by default curl uses the GET method. Now let’s move on to using POST.

With the POST method, the request includes a body payload. I’ll take an example to make it easier to understand: let’s say there is a /login endpoint. After we know the values of the username and password fields are user and pass (which we can see by using curl above to retrieve the source of the login index page), I will use curl to log in to the application.

Hmm, some of you might think: why use the CLI to log in to an application? The purpose here is to obtain the session cookie so that we can perform a series of actions after logging in—such as listing users if this account has the permission, or exploiting various types of web attacks like submitting reports or similar actions that can only be performed after login.

I think some of you might ask again: if that’s the case, why not just use a GUI and Burp Suite for faster work? Hmm, I honestly don’t know how to answer that, so let’s just keep going—you might need this at some point.

Ok, back to using POST with a body payload. The structure of this example will be as follows:

curl -i -X POST -d “user=alonewofl&pass=123456” https://SERVER_IP/login

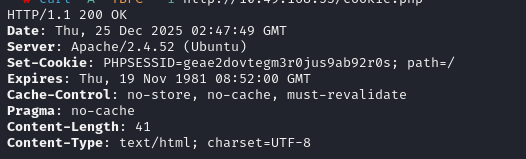

Okay, after I get a response that contains the cookie header, I will save this value into a text file or something similar, then perform some slightly manual steps to keep this session cookie for subsequent requests. If you use a browser, the cookie will be sent automatically.